The Composite Materials Failure Index in Abaqus

Knowing the material limits in terms of structural strength is paramount to assess if a given structure can withstand the loads for which it is designed, and which reserve it has to allow for unexpected higher loads.

If for ductile materials this process is very well consolidated and generally based on the Von Mises stress that needs to be below the yield limit of the material (this is not the place where to discuss about plasticity and ultimate failure) by a given Reserve Factor, for composite materials, especially those with long and oriented fibers, the question is much less trivial.

Different failure criteria exist for composites and none of them seems to be best; every Structural Engineer and/or company have their preferred ones, always based on their own past experiences and on the kind of fiber/resin system they have worked with, making practically impossible to come to a general rule.

The most used criteria for composite materials are Max Stress, Tsai-Hill, Tsai-Wu and Hoffmann and, very similarly to the Von Mises criterion, they combine, a part for the Max Stress one, the stress components in order to generate a “number” indicating the potential failure.

This number is called “Failure Index” (FI): if FI = 1.0, then there is failure, if FI < 1.0 then the structure is “safe”. The problem with this is that it is not possible to say straightforward by “how much” it is safe, because in the above mentioned criteria the stresses are combined with non-linear relationships; unique exception is the Max Stress criterion: if we use this, then to get the Reserve Factor we can simply invert the FI obtained.

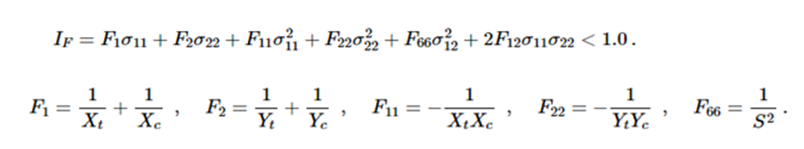

Let’s focus on the Tsai-Wu criterion, reported in Figure 1.

Xt, Xc, Yt and Yc are the allowable stresses in the fiber direction (X) for tension (t) and compression (c) and for the transversal direction (Y) for tension (t) and compression (c); compression values are to be considered negative numbers.

S is the shear allowable stress.

F12 can be considered equal to zero as a first approximation.

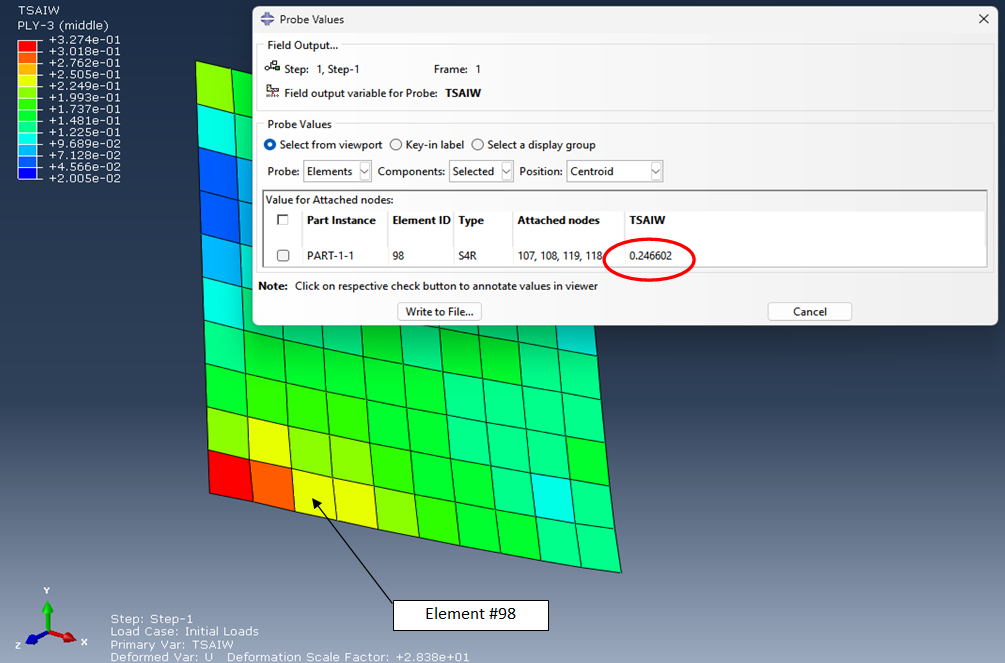

So if now we create a model of a composite plate (four plies: 0/45/45/0) and we apply to it a set of forces, we get from Abaqus the Tsai-Wu “numbers” illustrated in Figure 2 (ply #3).

Focusing on element #98, we see that the Twai-Wu “number” is 0.246602.

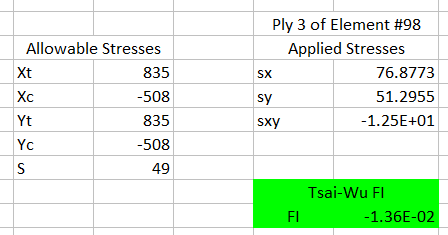

Taking from Abaqus the stress values for ply 3 on element #98 and calculating the Tsai-Wu FI using the relationship of Figure 1 we expect to get the same number. We do that with an Excel file, as shown in Figure 3.

As it can be seen, we get a much different number (-0.0136 vs. 0.246602).

What has happened? Who is wrong?

The answer is: nobody.

The reason of the huge difference has to be searched in the way Abaqus deals with the failure quantities calculated for composites. Remember what we said above about the uncertainty given by the Failure criteria that cannot easily indicate by “how much” a structure is safe?

Well, Abaqus sorts this out for us and the number it outputs when dealing with composites materials is already the inverse of the Reserve Factor we are use to deal with.

Therefore Abaqus does it differently than other codes, such as Nastran, that output the Failure Index exactly in the way we calculated it with the Excel file of Figure 3.

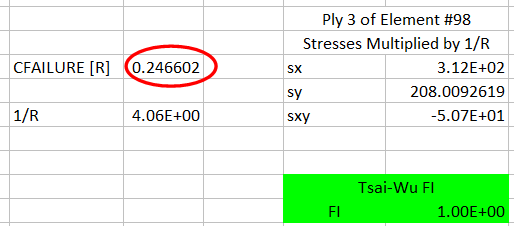

To close the loop, let’s multiply the stresses by 1/0.246602 and recalculate the Tsai-Wu FI, again with the help from Excel.

As it can be seen from Figure 4, now the Failure Index is 1.0, as it should be having multiplied the stresses by the Reserve Factor.

This fact is documented in the Abaqus User’s guide, but it might be overlooked by users that have experience with other codes.

More on Failure Indeces and Composite Material calculations can be found at Chapter 8 of the book “Computational Structural Engineering” .