Post-pioneering in Mechanical Structural Analysis with Finite Elements Models

My generation of Structural Engineers (graduated in the early ’90s of last century) in the mechanical field were post-pioneers in computation with Finite Elements. I say this because they found themselves operating in an industrial environment that was not at all ready to include in the design cycle a phase whose usefulness entrepreneurs struggled to understand, especially in light of the enormous costs that hardware and software manufacturers were demanding. And so the saying “it has always been done this way” dictated the law.

In aerospace, things were a little different: just under thirty years earlier, this industry had been the real pioneer in implementing this technology, and the first commercial version of NASTRAN (NAsa STRuctural ANalysis) was in 1971. The aerospace industry, therefore, was already fully aware of the limitations and advantages that the numerical approach to calculating structures brought.

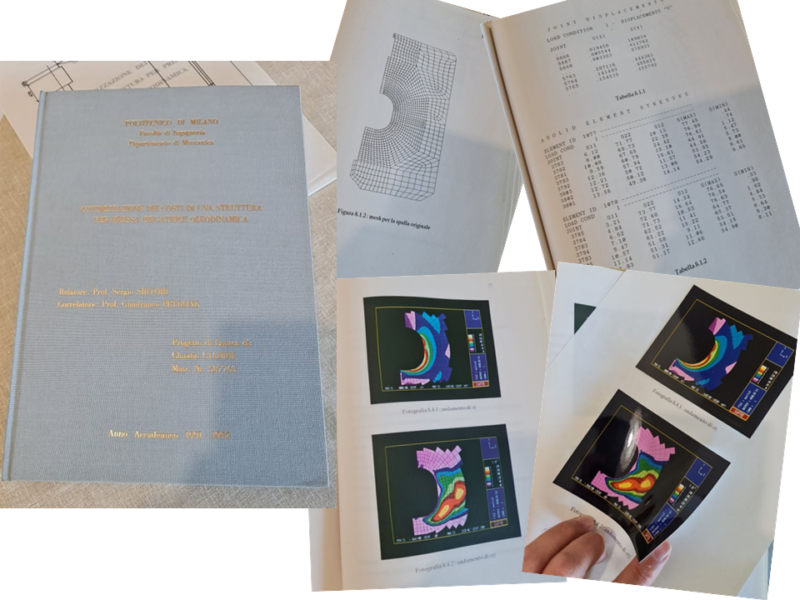

However, the ’90s were also the years when PCs were beginning to have computing powers of some significance, and computer graphics was making huge progress to the point where it began to be possible to build Finite Element models no longer just on graph paper, but also interactively within specific graphics software. Similarly, the reading of results, previously done through printed tabulates, could now be visualized with bands of color “smeared” across the object being analyzed.

While this made the advantages brought by Finite Element models more obvious to the more “ illuminated” entrepreneurs, it also raised doubts in the more skeptical ones that the “color results” were merely appearance and no substance.

History, however, tells us how things went and today we can say with certainty that the complexity of the Finite Element models we find in the mechanical industry has overcome that of the models of the aerospace industry (for reasons that it is not the case to recall in here) and that any entrepreneur or business manager has, sooner or later, included in the design cycle of his products the simulation phase (as it is called today) either by bringing it directly within his technical offices or by outsourcing it to specialized external companies.

The figures show some images from my Master’s thesis: the color maps gave a general idea of the stress trend, but the actual value still had to be searched in an ASCII file.

La mia generazione di Ingegneri Strutturisti (laureati agli inizi degli anni ’90 del secolo scorso) in ambito meccanico sono stati dei post-pionieri nel calcolo con gli Elementi Finiti. Dico questo perché si sono trovati a operare in un contesto industriale che non era per nulla pronto a inserire nel ciclo di progettazione una fase di cui faticavano a comprendere l’utilità, soprattutto alla luce dei costi enormi che i produttori di hardware e software chiedevano. E così il detto “si è sempre fatto così” dettava legge.

In ambito aerospaziale le cose erano un po’ diverse: poco meno di trent’anni prima il settore era stato il vero pioniere a implementare questa tecnologia e la prima versione commerciale di NASTRAN (NAsa STRuctural ANalysis) è del 1971. L’industria aerospaziale, dunque, era già pienamente consapevole dei limiti e dei vantaggi che l’approccio numerico al calcolo delle strutture portava con sé.

Gli anni ’90 furono però anche quelli in cui i PC cominciavano ad avere potenze di calcolo di un certo rilievo e la computer graphic stava facendo passi enormi fino al punto che cominciò a essere possibile realizzare modelli a Elementi Finiti non più solamente sulla carta millimetrata, ma anche in modo interattivo all’interno di specifici software grafici. Allo stesso modo la lettura dei risultati, prima fatta attraverso tabulati stampati, poteva ora essere visualizzata con bande di colore “spalmate” sull’oggetto analizzato.

Questo, se da un lato ha reso più evidenti agli imprenditori più “illuminati” i vantaggi portati dai modelli a Elementi Finiti, dall’altro ha anche sollevato in quelli più scettici il dubbio che i “risultati a colori” fossero solamente apparenza e niente sostanza.

La storia, tuttavia, ci racconta come sono andate le cose e oggi possiamo affermare con certezza che la complessità dei modelli a Elementi Finiti che troviamo nell’industria meccanica ha superato quella dei modelli dell’industria aerospaziale (per motivi che in questa sede non è il caso di richiamare) e che qualunque imprenditore o manager aziendale ha, presto o tardi, incluso nel ciclo di progettazione dei suoi prodotti la fase di simulazione (come oggi viene chiamata) o portandola direttamente all’interno dei suoi uffici tecnici oppure demandandola a società esterne specializzate.

Le figure mostrano alcune immagini tratte dalla mia tesi di Laurea: le mappe di colore davano un’idea generale dell’andamento dello stress, ma il valore effettivo andava ancora ricercato in un file ASCII.